What is the Tamborrada in San Sebastián?

Ay the tamborrada. It’s that time of year again, January 20, the day of San Sebastián. Where the city erupts into a gigantic, slightly indecipherable party, and groups of locals form street parades, dress as soldiers and cooks, and march for 24 hours straight. I would normally be taking part in this, but for the last two years, the COVID pandemic has always been raging in the dead of winter, and 2022 is no exception. So I’m dedicating the hours I would spend eating, drinking wine then patxaran then gin tonic all night before collapsing into bed for a few hours at dawn only to do it all again later in the day to…writing this blog post. It’s a party worth explaining, so here goes.

What is the Tamborrada?

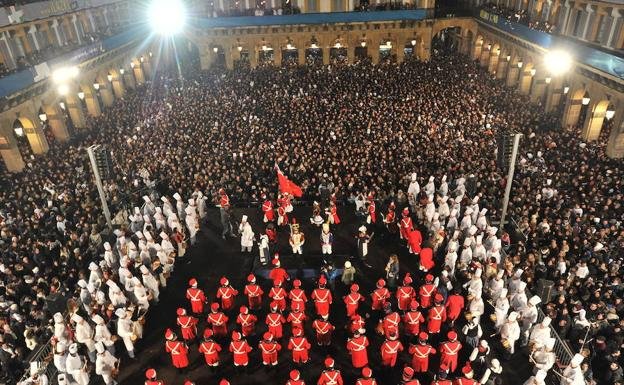

As I mentioned above, the tamborrada is, at its most basic, a celebration. The tamborrada is celebrated on the day of San Sebastián, January 20, in San Sebastián, the capital of the Basque province of Gipuzkoa. The party starts officially at midnight in the Plaza de la Constitución—the flag is raised in an act known as the izada, and one group of drum players (the members of the Gaztelubide dining society) begin to play the “Marcha de San Sebastián” (see below) and then all the groups join in and take off on their route throughout the city. The drumming continues for the next 24 hours, all across the city, as groups take their turns marching (even at 4am, gasp! even at 3pm when everyone decent is eating lunch, double gasp!) along to keep the sound of the drums going. Participants are dressed either as cooks or in period soldier clothing, a nod to the fight the citizenry gave to the Napoleonic troops that tried to take over the city.

During the day of the 20th, the children have their own tamborrada, the tamborrada infantil. At noon, the groups from many schools in San Sebastián, both public and private, begin to march from the Town Hall and parents line the streets, proud and merry, probably with a vermouth or wine in hand.

A bit before midnight on the 20th, the party begins to wind down, back in the Plaza de la Constitución. The group from Unión Artesana, another one of the oldest and most prestigious dining societies in the city, plays the march again and the flag comes down.

The Tambor de Oro, or the Golden Drum, is another big part of the festival. This award is for those who have promoted San Sebastián across the world and is considered the highest honor (pick me pick me! haha).

Why do we celebrate the TamboRRADA?

Basically, it’s a celebration of the Day of San Sebastián. Nowadays, it is an expression of patriotism, or the closest thing you can get to it, by the residents of San Sebastián. It’s a point of pride. Being involved in a group of drummers is considered a big plus in your street cred column, the closer to the Old Part and midnight on the 19th, the better. Everyone gets emotional during the celebration, and the dinner the night before is a huge deal for many families. In fact, it’s one of the only nights of the year people splurge on luxury seafood like angulas, or baby eels (elvers).

The real reason why the tamborrada is celebrated the way it is, though, is a bit more complicated.

Tamborradas. Tamborrada infantil a su paso por el Boulevard, calle Hernani y el puerto por donde también desfila la carroza de la Reina de San Sebastián con sus damas de honor Source: https://www.kutxateka.eus/Detail/objects/197924/s/0

What is the history of the tamborrada?

Don’t you love origin stories that begin with “Nobody knows the origin of….”? So satisfying, right? Well, nobody knows the true origin and the actual date of the first tamborrada. There, I said it. That said, there is a lot of actual history and, of course, a neat and easy origin story to tell children, tourists, and adults that don’t like complexity.

In 1597, there was a plague (sound familiar) that forced the residents of San Sebastián to isolate themselves from other villages. The parishioners of San Sebastián went to pray to Saint Sebastian, who JUST SO HAPPENS to be the patron saints of epidimics/pandemics/plagues/etc. Well, it may have been the fire they used to burn all of Pasajes (the most infected area), or it may have been that the sickness became endemic, but IT WORKED. They vowed to celebrate this every year, fasting the 19th and holding a procession on the 20th. And some trace the beginning of the Tamborrada that far back.

They tried to change the festival to summer in 1820 because of bad weather (this story is just too relatable) but no dice.

The tradition of the izada is known to date back to 1924, but the first chronicles of a celebration called Tamborrada are from the 1830s. The city was invaded and dominated by the military, and the residents would watch them parade from the barracks of San Telmo to what is now the Boulevard for the changing of the guard. They say that the service girls, soldiers and working people would drum on the horseshoes and barrels as they waited their turn to draw water from the city fountains. This is the imagery we see in today’s tamborrada.

Then, the slightly less romantic story goes that it all stems from a carnival group, and just sort of merged into the celebrations of San Sebastián. It seems that the participants first dressed in random costumes before switching to the cooks and soldiers theme we know today, which supports the theory. It is said they would march from 3:30 in the morning from La Fraternal society until 8 o’clock. Later, La Fraternal became the Unión Artesana (in 1870), and they continued the tradition (all the way to 1956) of leaving at 5 am and marching through the morning. They were the ones to incorporate the costumes belonging to the Napoleonic wars. Cans and wood were replaced by drums, barrels and water buckets.

In 1906, Euskal Billera formed a tamborrada, and all the tamborradas decided to play together, which is when this all really began to look like the modern festival. The societies included the Unión Artesana, Club Cantábrico, Sporti Clai, Amistad Donostiarra and Euskal Billera. The children’s tamborrada, another vital part of the festival, had its initial start in 1927. Now it consists of over 50 groups and over 5,000 children.

The modern tamborrada has evolved in so many ways. It’s now much more organized. Women are allowed to participate. The first male-female tamborrada was Kresala Elkartea in 1980 (more below), featuring a new figure, the water girl (aguadora). It involves the whole city, not just the dining societies. The start of the festival being the Plaza de Constitución and the raising of the flag as an official act only really dates back to 1999.

Women in the tamborrada

This topic has been a controversial one since the days of women’s rights. Of the over 150 groups that participate in the Tamborrada, 10 of them still do not allow women to participate. It used to be more, but there has been an increasing movement to allow their participation, and now it is viewed as normal. The exclusion of women comes from the fact that they were also, until relatively recently, excluded from the dining societies, which form the basis of the drumming groups.

It is believed that women, when the tamborrada was the more informal, carnival-esque affair, did participate. However, as the tamborrada became more and more serious, and linked to dining societies, women were excluded. The key moments in the sea change back towards equality in the celebration began with the incorporation of women by Kresala Elkartea in 1980, although it was with a new female figure, the aguadora. In 1982, in another club, they were allowed to wear the traditionally male costumes. In 1984, they were allowed to participate in the children’s tamborrada as long as they didn’t “let their long hair and earrings show”. There was a huge controversy when the Tambor de Oro was given to a woman for the first time, yet she was not allowed in the traditional celebratory dinner at Gaztelubide. You can see the change towards having male-female tamborradas in the above graph. In 2005 there was an Equality Law approved by the Basque Parliament, which is where the dial really begins to move.

You can find more information on the gender issue in this fascinating book.

Source : Kutxateka (1936) and Diario Vasco (2016)

Should I visit san sebastián during the tamborrada?

The answer is a strong…maybe. January 19-20th is a time where you will see the city alive, the citizens at their happiest, that is for sure. My theory, however, is that all these parties in the dead of winter exist to keep everyone’s mental health from nose diving, because winter here is HORRIBLE. Cold, yes, kind of, but mostly very rainy. So, rain and cold is something you must be prepared to endure if you are planning a visit to San Sebastián during the tamborrada.

Another point to consider is the fact that this is quite the insider’s fiesta. In the words of Javier Maria Sada, “He who sees, today, in the tamborrada a group parading through the streets playing a kalejira, is as far from appreciating all of its value as he who is content to read merely the cover of a book, ignoring what’s inside.” In other words, nanabooboo, you’re never going to get it! That said, it’s still a fun night and day, the streets filled with people.

Perhaps the biggest argument for visiting on January 20? It is the one day of the year that the dining societies of they city open their doors and let anyone in. That in and of itself could be motivation for some.

GORA DONOSTI! DONOSTI BAT BAKARRA MUNDUAN!!!

I leave you with the words to the march of San Sebastián:

Bagera!

gu (e)re bai

gu beti pozez, beti alai!

Sebastian bat bada zeruan

Donostia bat bakarra munduan

hura da santua ta hau da herria

horra zer den gure Donostia!

Irutxuloko, Gaztelupeko

Joxemaritar zahar eta gazte

Joxemaritar zahar eta gazte

kalerik kale danborra joaz

umore ona zabaltzen hor dihoaz Joxemari!

Gaurtandik gerora penak zokora

Festara! Dantzara!

Donostiarrei oihu egitera gatoz pozaldiz!

Inauteriak datoz!

Bagera!

gu ere bai

gu beti pozez, beti alai!

-La Marcha de San Sebastián (1961, Raimundo Sarriegi)

Source: abc.es